FEATURE ARTICLES

The "Prophet" Isaac Bullard and his

fanatical Modern Pilgrims: 1817-18

1973 F. G. Ham article | 1969 N. F. Schneider article | Bibliography | Comments

|

Where was Sidney Rigdon During Sidney's early adolescence revival ferment was still in full swing in western Pennsylvania, and from a young age he likely attended Peters Creek Baptist Church. His own account, given in 1869, simply says, "[I] became acquainted with a Baptist minister" [who called my] attention to personal religion." (Moore's Rural New Yorker 1869, 61). Whether Sidney Rigdon's May, 1817 Christian conversion "experience" was real or "made up one to suit the purpose," his subsequent religious career, with "so much miracle" involved, indicates that his interest might have been drawn to a news item that appeared in his local newspaper, later that same year: I noticed in one of your late papers some account of several pilgrims who were then in New Jersey, on their way from Woodstock, Vermont, to the South. Their pilgrimage, it appears, commenced in Lower Canada, I believe in May or June last... At Woodstock, in the state of Vermont, they successively arrived, and tarried several weeks -- made some proselytes, and otherwise added to their numbers. Beneath the roof of a Christian preacher, their devout professions procured them a hospitable protection; and so incessant were their professed addresses to and communications with invisible beings, with whom they pretended at times to hold converse... their fame went abroad -- Pitsburgh Gazette Nov. 4, 1817 And, if the young Baptist convert had been particularly alert to unusual happenings in his neck of the woods, he might also have heard fresh reports that these same "pilgrims" who "professed addresses to and communications with invisible beings" were then passing through the Pittsburgh area, on their way to Mount Pleasant Ohio and points west.  The old Courthouse in Woodstock, Vermont History does not record whether the newly converted Rigdon rushed out to gape at these passing religious fanatics, at the end of October, 1817. Presumably he was then still living on his late father's farm, adjacent to Library, Allegheny Co., Pennsylvania, and the "Vermont Pilgrims" passed within a few short miles of his own residence. One writer who followed the progress of these unusual saints through the Pittsburgh area had this to say about their presence there: The 'Pilgrims' arrived at Pittsburgh in the autumn of [1817], and were accomodated for the time with an out-building belonging to Mr. H____. The general curiosity of that city was excited upon their arrival, and every one was anxious to be gratified with the sight of so novel a sect. Some, that were more curious and who suspected the sincerity of their religion, watched them, unobserved, at hours when it might be supposed they would commit themselves; nor were they disappointed. Many anecdotes are related of them in Pittsburgh, which would represent them as the most abject creatures of the vilest fanaticism. -- They did not embark at Pittsburgh. They travelled through the interior. If Sidney Rigdon did take the trouble to join in on this "general curiosity," and did go out to encounter the remnant of "the lost tribe of Judah," on its way to a millennial promised land in the west, his excitable nature would have no doubt been stimulated to new heights of enthusiasm. Even without their pretended "Prophet," Isaac Bullard (who was then leading a separate band of followers through New York to an eastern Ohio rendezvous), the band of fanatics must have presented a sight seldom seen and never forgotten. And, even if they did not announce all of the details of their Christian communitarianism, their spirtual wifery and their continual reception of modern divine revelation, the Pilgrims' prophetic exclusivity and their claims to a restoration of spiritual gifts could not have escaped his notice. For weeks and months thereafter, newspaper readers continued to follow published reports of the progress of "Prophet" Isaac Bullard and his latter day saints on their southwestward journey -- the publicity they managed to generate during the last months of 1817, on into the early 1820s, was nothing short of miraculous.

Years later, a Woodstock Vermont newspaper editor remarked upon what it called "The Mormon Deluson," as follows: "Our readers will recollect a similar delusion which raged some ten years ago in the case of the 'Pilgrims.' Their Prophet -- Old Isaac, as he was called -- came from Canada with a few, and encamped in Woodstock. Here outraging not Christianity only but humanity, by their absurd opinions and absurder practice -- by taking the assertions of their infatuated leader for divine revelation... they induced many decent people who should have known better to join them, under the empty practice of being led to the holy land... From the resemblance between the Pilgrims and the Mormonites in manners and pretensions, we should think Old Isaac had re-appeared in the person of Joe Smith, and was intending to make another speculation." -- Vermont Chronicle June 24, 1831. Just prior to the first appearance of Mormonism in western New York, the Palmyra Wayne Sentinel (at which print shop the Book of Mormon was subsequently published), informed its readers: "Bullard, (called also by his followers, the Prophet Elijah,)... Before he began his mission, he had a severe spell of sickness, when he fasted 40 days, (as he said, and his disciples believed;) after which he recovered very suddenly, by the special interposition of the Divine Spirit, and being filled with enthusiasm, he declared that he was commanded to plant the church of the Redeemer in the wilderness... This fete of folly and delusion, is perhaps worthy of notice, as furnishing a striking instance of the blindness of credulity -- the wilderness of fanaticism, and the miserable propensity of the mind, to believe itself possessed of powers which do not belong to humanity." -- Wayne Sentinel May 26, 1826 What "pointers" (if any) religious-minded men like Sidney Rigdon and Joseph Smith, Jr. may have taken from the "Prophet" Isaac Bullard and his deluded band of followers, History does not record. There are both unique similarities and marked differences between the Mormons and the Pilgrims. While both groups of exclusive restorationists managed to gain new converts, by claiming to be the one true church, with signs and wonders following, the Vermont Pilgrims never managed to established their western New Jerusalem, nor to publish Bullard's revelations to the world. Despite their early success at generating intense public interest, the Pilgrims were a transitory phenomenon and soon forgotten -- the Mormons, on the other hand, became permanent and forever a presence in the public consciousness. An early biographer of Joseph Smith called Bullard's fanatical band of 1817-18 "a strange prototype of the Mormon movement" in which the Pilgrims' leader "asserted that he was a prophet and claimed immediate inspiration from heaven. Property was held in common and the leader controlled all the affairs of his followers..." (I. Woodbridge Riley's The Founder of Mormonism p. 46). It may be relevant to here recall the Sidney Rigdon himself instituted a Mormon commune near Greencastle, PA, in 1845. Rigdon's followers were not so faithful as had been those of Isaac Bullard, and the Rigdonite commune was a short lived failure. Whether the "Modern Pilgrims" were indeed a "Mormon prototype," or merely a largely unrelated precursor, the story of Isaac Bullard's short-lived movement is presented here, as a source for religious comparisons and as a stimulus for additional research. |

Reprinted with permission of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

© 1973 The State Historical Society of Wisconsin -- used with permission [ 290 ] ON September 10, 1817, the startled inhabitants of Newton in Sussex County, New Jersey, looked on in unbelief as a group of ten pilgrims from Woodstock, Vermont, passed through the town on their way west to what they hoped would be the promised land. One observer, whose account of the sect appeared in the Sussex Register a few days later, noted that the sect was "possessed of a very singular appearance and deportment.... They ask no charity; move very slow, with a cart yoke of oxen and one horse, and say the Lord will provide for them, for where they go, there He is. Their dress is very singular, long beards, close caps, and bear skins tied around them. The writer believes them a set of deluded enthusiasts." 1 As newspapers from New England to the Missouri Territory reprinted the article, the Vermont Pilgrims, the most bizarre and primitive sect in American religious history, appeared on the national kaleidescope. Most Americans in that lackluster year, which the Boston Columbian Sentinel not altogether aptly labeled the beginning of the "era of good feelings," were caught up in the dominant currents of resurging nationalism, westward expansion, and post-war prosperity. Yet as the perceptive Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville noted a decade later, in an acquisitive society where the "great majority of mankind were exclusively bent upon the pursuit of material objects," certain momentary outbreaks occurred when small groups of individual souls "seem suddenly to burst the bonds of matter by which they are restrained, and soar impetuously toward heaven." 2 Most of these flights of religious ultraism were concentrated along a "psychic highway" that stretched from the backcountry of New England, across the undulating plains of western New York -- "The Burned-over District" -- into Ohio. Along this broad belt of land, observed Whitney Cross, the historian of enthusiastic religion in this area, there "congregated a people extraordinarily given to unusual beliefs, peculiarly devoted to crusades aimed at the perfections of mankind and the attainment of millennial happiness." 3 The source of religious ultraism -- evangelical revivalism -- was deeply embedded in the life of the times. Throughout this area small groups of "come outers," "New Lights," "Mercy Dancers," and other anti-Calvinist radicals did battle with the conservative Congregationalists and Presbyterians, while the constant agitation of such theological questions as free will, human ability, perfectionism, and millennialism, produced a climate in which fanaticism thrived. 4 __________ 1 Sussex Register (Newton, New Jersey), September 15, 1817. 2 Alexis de Tocqueville, DEmocracy in America, translated by Henry Reeve and edited by Henry Steele Commager (New York and London, 1947), 342, 343. 3 Whitney R. Cross, The Burned-over District: The social and Intellectual History of Enthusiastic Religion in Western New York (Ithaca, 1950), 3. 4 In addition to CRoss's thorough study there is an excellent but brief essay on the impact of left-wing evangelical revivalism on religious rasicalism and communtarianism in America, in Stow Persons' essay, "Christian Communitarianism in America," in Donald Drew Egbert and Stow Persons (eds.), Socialism and American Life (Princeton, 1952), I: 127-151. [ 291 ] There were rumors of strange occurences in Yates County in Western New York where the self-styled prophetess, Jemima Wilkinson had parlayed celibacy and equality of the sexes into a communitarian society known as the Community of the Publick Universal Friend. Farther west along the banks of the Ohio near Marietta, Abel Morgan Sarjant, a renegade Universalist preacher, founded his Halcyon Empire in 1801. With his twelve apostles, "mostly women," God's Millennial Messenger, as Sarjant styled himself, toured the Ohio Valley preaching the annihilation of the wicked and proclaiming that Christ's thousand-year reign on earth had begun. Sarjant's followers, who were organized into units called "tribes," believed they could achieve immortality by fasting. The Halcyons reduced their food quotient to "three kernals a day," but when one of the members died "for want of food" the movement collapsed. 5 Few states assyed higher in fanaticism than Vermont, "a land of strange delusions." Her citizens were already well known for their religious as well as their political heterodoxy, and the intense religious ferment in the area made it a spawning ground for such new messiahs as the Mormon seer Joseph Smith, the Oneida Perfectionist John Humphrey Noyes, and that great "Watcher for the Second Coming," William Miller. 6 Finally, standing out as a kind of ultimate among enthusiatic movements were the "Shaking Quakers." Combining in microcosm nearly every radicalism of the day, Shakerism had a persuasive appeal to those disenchanted seekers left in the wake of recurring revivals and religious enthusiasms. For many spiritually dispossed souls, the Shaker villages that dotted the rural landscape in western New England, upper New York, and the Ohio Valley, often became a port of last call. 7 It was from this religiously infectious atmosphere of evangelical revivalism tinged with the radical doctrines of millenarianism and perfectionism that the Vermont Pilgrims and their charismatic leader, the minor prophet Isaac Bullard, emerged. The society had its rise in the British Dominions to the north, at Ascot in the Compton District of Lower Canada near the forks of the River St. Francis, some thirty-five miles above the Vermont border, a point which some Anglophobic and religiously orthodox Vermonters were not remiss to make. 8 Typical of the "come-outers" and spiritually dispossessed of the epoch, the Pilgrims were in revolt against the prevailing denominationalism of the time. They viewed the established churches as being formal, lacking in piety and inspirational warmth, and corrupt. With a romantic yearning for the lost simplicity, universality, and purity of the primitive New Testament Church, these restorationers separated themselves in the hope of forming a more holy and perfect communion after the apostolic model of the Book of Acts. 9 The Prophet, "a compound, like the character of Cromwell, of hypocrite and enthusiast," was a man of "Elegant figure" who sported a red beard of "superior length." Those who knew him in Lower Canada testified to his good character and noted that his talents were "much above the middle class of citizens." After joining this society of the simple in faith and pure in heart, he easily rose to a position of leadership, although at the time one correspondent learned that Bullard did not "believe himself possessed of the powers he professed." Like any prophet worth his salt, he received divine revelation and professed to govern by immediate inspiration from Heaven. His authority was unquestioned, __________ 5 Cross, The Burned-over District, 33-36; F. Gerald Ham, "Shakerism in the Old West" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Kentucky, 1961), 278-281. 6 See David M. Ludlum, Social Ferment in Vermont, 1781-1850 (New York, 1939), 238-260. 7 Cross, The Burned-over District, 32; Ham, "Shakerism in the Old West," 261-286. 8 Ira Chase to the Secretary of the Massachusetts Baptist Missionary Society, Clarksburg, [West] Virginia, January 6, 1818, in The American Baptist Magazine, I:342 (May, 1818); Zadock Thompson, History of Vermont, Natural, Civil, and Statistical (Burlington, 1853), Part II:203; North Star (Danville, Vermont), May 22, 1818. 9 Sussex Register, September 15, 1817; Timothy Flint, Recollections of the Last Ten Years, Passed in Occasional Residences and Journeyings in the Valley of the Mississippi (New York, 1968), 275. [ 292 ] and he ruled "the sect as an absolute monarch in all things spiritual and secular." 10 The pentecostal seed of Bullard's gospel fell on arid soil. Failing to make headway in Canada, the Pilgrims disposed of their more encumbering earthly treasures and prepared to move to Vermont. Reportedly, the trek was given an air of immediacy when the fulfilling of a divine edict landed the Pilgrims in the King's courts. The charge was murder; the victim, an infant who had been given a decoction of poisonous bark "by command of the Lord." The court found the evidence against the saints inconclusive, but the Pilgrims' less judicially minded neighbors were of a contrary opinion. A forced march over the border became the "last resort" of this new sect. 11 In 1817 the dormant embers of revivalism had flared anew in Vermont as the tired band of Pilgrims marched into the Connecticut River Valley town of South Woodstock, in May or June. Accompanying the Prophet were his wife and an infant son -- an alleged holy child who was called "Christ" or the "Second Christ" -- and about six faithful followers. Here in a "back and retired part of town" Bullard found "materials suited to his purpose." Among the first to succomb to the Prophet's persuasive message was the Reverend Joseph Ball, a humble and affable minister of the "Christian" connection, a radical anti-Calvinist sect which, stressing liberty of conscience and freedom from creeds, had organized at Lyndon, Vermont, about 1802. 12 Equally fortunate for the struggling sect was a conversion of Ball's brother Peter, for he had both a small farm and a large family. Simultaneously, the Prophet had acquired converts and a base of operations. From this "hospitable protection" Bullard conducted proselyting forays into Woodstock and neighboring towns. Within a short time, a number of simple "unsuspecting souls," including a few of "respectability and property" were led into the Prophet's "snares." By mid-summer Bullard's ranks had swelled to nearly forty converts, and the local postmaster, Alexander Hutchinson, noted that none joined the sect but such as "were made to believe that Isaac had power to make the most miserable of human beings, and that nothing short of their joining him would prevent the exercise of his power upon them -- and they in that belief became insane in a degree," 13 Bullard never committed his beliefs to writing, and contemporary inquirers found it all but impossible to engage the Prophet's followers in a discourse of their strange beliefs. Their restorationist gospel, however, differed little from the other chiliastic sects that spring up around the lurid fringes of evangelical revivalism. The Pilgrims rejected sectarian distinctions, abhored ritualism, were intensely anticlerical, and abandoned many of the sacraments. They relied on intuition, immediate inspiration, and revelation rather than on the Bible and systematic credal formulations to certify correct practice and sound doctrine. As the only true followers of Christ, these rustic pentecostals believed they were commisioned by the Almighty to go forth into the unregenerated world to do His will. To this end they had forsaken their homes, lands, friends, and "all this world's enjoyments," and in imitation of the nomadic practices of the "ancient patriarchs and good men of old," went from place to place doing good unto the children of men. Like many religious radicals of the day they held to the belief in the nearness of a millennial society in which man at last could triumph over sin and realize the ideal of Christian perfection. Even now the lost tribes of Judah -- which held a strange fascination for many an American prophet -- __________ 10 Ibid, 276; The Philanthropist (Mount PLeasant, Ohio), January 2, 1818; American Baptist Magazine, I:342. 11 Thompson, History of Vermont, II:203; Flint, Recollections, 275; Virginia Patriot (Richmond), quoted in the Pittsburgh Gazette, November 4, 1817. 12 Ludlum, Social Ferment in Vermont, 35-36, 242-243; Records Kept by Order of the Church [New Lebanon, New York], 1780-1855, p. 51, in Shaker Manuscript No. 7, New York Public Library; Thompson, History of Vermont, II: 203; American Baptist Magazine, I:341. 13 Thompson, History of Vermont, II: 203; Pittsburgh Gazette, November 4, 1817; Rutland Herald, quoted in the American Yeoman (Brattleboro), October 14, 1817; The Philanthropist, January 2, 1818. [ 293 ] were "beginning to be gathered in;" and, to hear the Pilgrims tell it, the way was fast opening when the "four quarters of the earth" would be brought together in a universal communion. 14 But how was the errant man to achieve the state of sinless purity that the prospect of the millennial kingdom seemed to demand? Bullard, like most anti-Calvinist radicals of the time, found the answer in a typically American counterpoise to a stern and deterministic Calvinism -- in a covenant of works that stressed voluntarism and human ability. Rather than waiting and hoping God would flood his soul with irrestible grace, the pennitent sinner must be an active participant in achieving his own slavation. Largely by his own efforts, he must strive for a life of sinless purity. The transition from a life of carnality to one of perfect holiness was marked by tribulation and travail. In this work of regeneration Isaac Bullard called his followers to a life of repentance, poverty, and rigorous self-denial. Harsh penances were imposed on the contrite sinner corresponding to the state or degree of perfection he had achieved. The newly converted, for example, might be made to stand erect for as long as four successive days without sleeping or sitting. Possibly a couple of days fasting might also turn the trick. Indeed, fasting was the primary mode of penance, "both as severe in itself, and as economical." 15 Even the young were not exempt. When a young mother, "not quite destitute of feeling" for her infant "thirsting and weeping for some water" made supplication to the Prophet, he bellowed, "If it cannot fast let it die." 16 The most distinguishing feature of the Pilgrims' faith was the extreme primitivism that pervaded every facet of their daily lives. As an apostle of pentecostal simplicity, the Prophet was without a peer. He commanded his disciples to dispense with everything superfluous, "avoiding all sinful inventions of men and devils in dress and luxurious food." In addition to their bear skin girdles, on special occasions they wore sack cloth and ashes. 17 Their daily bread was a simple as their habit, consisting of a gruel of milk and mush or a broth of flour and water. Infrequently their diet was leavened with a piece of meat, but of course they did not eat much, for their leader kept them "most constantly fasting." These religious primitives found such ornaments of civilization as knives and forks and tables and chairs inimical to their spiritual welfare. They supped in a standing position, sucking up their meager repast through a perforated quill or cane stalk from a communal trough or bowl. 18 Not satisfied with these atavistic innovations, the red-bearded patriarch added an even more nauseating dimension to the apostolic faith -- that of filth. In his Biblical researches Bullard found no injunction to wash, so he forbade his followers to bathe or to cut or comb their hair. Again Bullard set the example. The saints alleged that their leader had not changed his skins for seven years. 19 "They are made to believe," declared one astounded onlooker, "that their filthy and ragged dress, their frugal, dirty and badly cooked food are meritorious; and to crown the whole, their eating it amidst & mingled, with the most naucious [sic] stench, monstorum horendum mirabile dictu." 20 But to the Pilgrims filth, fasting, and wretchedness were the keys to the kingdom. Their religious worship formed a pattern with their other habits and observances. Abasement of the individual personality was their aim. In an attempt to "mortify" the __________ 14 Interview with an unidentified Pilgrim, in The Farmer (Lebanon, Ohio), March 9, 1818; American Baptist Magazine, I:343; Pittsburgh Gazette, November 4, 1817; Thompson, History of Vermont, II: 203; Sussex Register, September 15, 1817, 15 The Farmer, March 9, 1818; John Hunt to James Sweny, August 20, 1874, undated newspaper clipping in Jisiah Morrow, Scrapbook of Lebanon and Warren County [Ohio], Concinnati Historical Society; Flint Recollections, 277. 16 Western Star, (Lebanon, Ohio) March 7, 1818. 17 Hunt to Sweny, August 20, 1874; Pittsburgh Gazette, November 4, 1817. 18 Flint Recollections, 277; Western Balance (Franklin, Tennessee), quoted in the Wayne Sentinel (Palmyra, New York), May 26, 1826; Hunt to Sweny, August 20, 1874; Records Kept by Order of the Church, New Lebanon, New York, 51; Urbana Gazette, quoted in The Farmer, February 7, 1818. 19 Thompson, History of Vermont, II: 203; Daily Advertiser (Albany) October 13, 1817. 20 Western Star, March 7, 1818. [ 294 ] carnal nature of the flesh, as they said, these early American "holy rollers" were often observed tumbling in the thick dust of the Vermont byways. In supplication to the Almighty, they prostrated themselves on the ground with their faces downward. 21 In their more formal worship, one correspondent reported, "The Prophet always takes the lead by making many singular gesticulations with his hands accompanied with a variety of unmeaning sounds, in which the muscles of his face, have many changes -- sometimes greatly extorted." His followers would then ape his every movement. Their unintelligible chants were characterized as "more ridiculous than the romantick folly of children or the pow wow of the savage wigwam." The New Lebanon Shakers gave them their euphonious name after listening to several choruses of the following chant: "My God, my God, my God, my God, What wouldst thou have me do? -- Mummyjum, mummyjum, mummyjum, mummyjum, mummyjum." 22 At Woodstock, Bullard instituted a rudimentary form of theocratic communitarianism. Though communal consciousness and social cohesiveness were undoubtedly stimulated by the hostility of the "gentiles," communalism among the Pilgrims was the child of necessity. Their nomadic life required some form of co-operation while only in a communal institution could the saints be properly disciplined, sustained in their arduous pursuit of a life of self-denial, and insulated from the unregenerate world. However, the subsequent migratory nature of the sect and the lack of a sustaining economic foundation such as distinguished the Shaker colonies and the German utopians at Economy in Pennsylvania and Zoar in Ohio made it impossible for the Prophet to develop a full-fledged disciplined communal institution. Documentation on community life among the Pilgrims is extremely fragmentary. The frintier missionary and literary publisher, Timothy Flint, learned that the sect was organized "to a considerable degree." The property of all who joined was put into a common stock, amounting to some $8,000 or $10,000. As the undisputed ruler, Bullard distributed the common stock as he saw fit. He also controlled his followers most intimate social relations, "marrying and unmarrying, rewarding and punishing, according to his sovereign pleasure." 23 Indeed, the social relations of the sect gave rise to salacious rumors that deloghted the orthodox. The Prophet, one newspaper reported, had abolished the marriage covenant allowing the saints to cohabit promiscuously, while "A friend of Christianity" found "some transactions" among the sect "which decency and chastity" forbade him to mention. Most likely Bullard did conjure up some form of spiritual wifedom, for one Shaker diarist learned "they pretend to marry a woman in God & by daoing [sic] sanctify the flesh." 24 By July or early August, 1817, Bullard had exploited the messainic potentialities of South Woodstock when, much to the relief of the local citizenry, he purportedly received a celestial communication to strike out for the promised land. The exodus was an uncertain journey, for the Pilgrims "knew not where they were going being led & directed by the spirit." According to later accounts, each morning Bullard would throw his staff on the ground to learn the direction of the day's travel. Unerringly, the staff always pointed to the southwest. 25 The story is probably legend, but there is no question that Bullard, like many of the social architects __________ 21 Thompson, History of Vermont, II: 203; Pittsburgh Gazette, November 4, 1817 22 Western Star, March 7, 1818; The Farmer, March 9, 1818; Records Kept by Order of the Church, New Lebanon, New York, 51; Nicholas Bennet's Journal, 1814-1833 [New Lebanon, New York], entry for August 25, 1817, Shaker Manuscripts, Western Reserve Historical Society. 23 Flint, Recollections, 277; Thompson, History of Vermont, II: 203. 24 Daily Advertiser, October 13, 1817; The Farmer, March 9, 1818; Records Kept by Order of the Church, New Lebanon, New York, 51-52; A Ch[urc]h Journal of current Events from Jan. 1st, 1816 to Oct. 10th, 1830 by John Wallace and Nathan Sharp [Union Village, Ohio], entry for March 11, 1818, Shaker Manuscripts, Western Reserve Historical Society. 25 Records Kept by Order of the Church, New Lebanon, New York, 51; Wayne Sentinel, May 26, 1825; Hunt to Sweny, August 20, 1874. [ 295 ] of the epoch, was lured on by a romantic vision of the glories of the American Garden of Eden, the transappalachain West. Surely, if God had [ever] prepared a primitive paradise where his chosen people would live in millennial happiness, the great American West was such a place. Slowly the peripatetic saints passed over the Green Mountains through Rutland and Bennington County where they welcomed a few more Vermonters into their fellowship. 26 On August 24, the caravan arrived at the prosperous Shaker village of New Lebanon, New York, nestled in the foothills of the Berkshire Mountains, some thirty miles southwest of Albany on the Massachusetts border. The official Shaker scribe noted: "Some of the company, particularly the females were by travelling & fasting, reduced to great weakness... and the whole company were very dirty & filthy; and by travelling in this manner they became very lousy." Why should Bullard and his saints seek out the sober Shakers? Like so many other social architects of the time, he probably wanted to learn of the "gospel order" as the Shakers called their increasingly well known and efficiently organized community life. Perhaps he also reasoned there might be some Shakers with a hearing ear who would forsake their vows of chastity and industry for the Pilgrims' offer of poverty and filth. Bullard, for his part, must have found the cleanliness, order, and industry of the Shakers revolting. The practice of celibacy was even less to his taste and because the astringent Shakers refused to allow the Prophet and his men to lodge "promiscuously with their women," the Pilgrims contemptuously refused the Shakers' kind offer of food and lodging; they cursed and "prophesied judgements" against their would-be benefactors. 27 Nevertheless, the brief contact with the Shakers reinforced Bullard's belief in the nearness of the millennial kingdom. One of his female followers wrote: "We began to preach that the coming of the Lord was at hand, that darkness had covered the land and gross darkness the people but God was now about to establish his kingdom on earth." 28 To broadcast this message of soot and salvation to the country, the Pilgrims divided into two companies apparently after leaving New Lebanon. The ox-cart brigade, mentioned in the Sussex Register, proceeded down the Hudson Valley, across northern New Jersey, and through Pennsylvania. On October 25 the Pittsburgh Gazette noted their presence in that bustling river town and learned that the destination of these "wretched fanatics" was the quiet Quaker hamlet of Mount Pleasant, Ohio, a few miles northwest of Wheeling, (West) Virginia. Here they apparently planned to await a rendezvous with the larger northern caravan led by Bullard and now moving across the Burned-over District of western New York. 29 Even the volatile Yorkers gaped in unbelief as this strange "caravan group for Mecca" passed through Troy and Cherry Valley slowly plodding westward towards the Finger Lake region in those warm autumn days of 1817. Leading the tattered band were the men, holding a short staff or stave in each hand which forced them to march with their bodies bent parallel to the earth. Their hunch-backed stance, long beards, "odd grimaces, incoherent language, and singular manouvers," wrote one observer, "gave them a very ludicrous appearance." 30 Bringing up the rear, the women and children followed in Indian file, with five horse-drawn wagons loaded with a limited supply of bedding, food, cooking utensils, and other household goods. Along the route the rag-tail saints could be heard exhorting the Yankee inhabitants to repentance and a life of poverty, pronouncing anathemas __________ 26 American Yeoman, October 14, 1817; Thompson, History of Vermont, II:204. 27 Records Kept by Order of the Church, New Lebanon, New York, 51-52. 28 Fanny Ball to the Brethren and Sisters at New Lebanon, April 30, 1820, in Union Village Shaker Letters, Western Reserve Historical Society. This letter, written by Peter Ball's wife, is the only known extant document written by a Pilgrim about their beliefs and their search for the promised land. 29 American Baptist Magazine, I:342; Pittsburgh Gazette, Octiber 28, 1817; The Philanthropist, January 2, 1818. 30 The Budget (Troy, New York), September 23, 1817; Daily Advertiser, October 13, 1817; Records Kept by Order of the Church, New Lebanon, New York, 52. [ 296 ] upon the scattered villages and their unregenerate citizens, or dolefully shanting, "Oh-a, Ho-a, Oh-a, Ho-a, Oh-a, Ho-a, My God, My God, My God!" 31 The Mummyjums went into temporary quarters on the land of a compassionate farmer near Dryden, a few miles east of Ithaca. Here they were visited by a Baptist cleric, Ira Chase, who left the only recorded account of community life among the Pilgrims. Their habitation was a crude and hastily bulit A-shaped lean-to affair. On the earthen floor at one end of the hut was their bedding, and along the sides of the quarters were chests and boards which served for chairs. Laid up overhead were two muskets "ready for use," and in the center of the room was a firee with a cooking pot hung over it. The Mummyjums, happily learning that Chase and his companion were members of the hated clerical caste, greeted them with "a tirrent of abuse, such as surpassed all that may be heard in the grog shop, from the lowest of the profane rabble." Bullard, in his only recorded monologue, told the visitirs, "O rotten! rotten! you go about living on the best fare you can find -- preaching pride -- with your white handkerchiefs, and black coats, as slick as a mole. -- Just as likely as not you spent half an hour in brushing them, when they were cleaner before than your characters. Hell and damnation, hell and damnation is your portion, if you don't repent." Gnashing their teeth and pointing the finger of scorn, the faithful chimed in, "Yah, yah, yah, yah!" The day previous Chase learned "they undertook, with the most frantic outcries, to expel Satan from the camp." He thought they had He thought they had not much success at it. 32 At Dryden, Chase noted the people were prepared "to embrace almost anything that is novel and extravagant." Here the Pilgrims made inroads among the "dancing Johnites" of another doomsday prophet, John Turner, who had recently paraded through the town of Dryden on a painted horse carrying a banner proudly proclaiming that the rider was none other than St. John the Divine. 33 During the winter the two companies were reunited somewhere in eastern Ohio. On March 1, 1818, after stopping at Zanesville, Mechanicsburg, Xenia, and other towns to do some proselytizing, they arrived at the Warren County town of Lebanon, twenty-three miles northeast of Cincinnati. To the dismay of the citizens, they made plans to stay until the spirit told Bullard to move on. Not only had the Pilgrims withstood the severity of the winter, but along the way they had recruited several converts. The band was now at a peak force of fifty-five. 34 During the course of the march, the Prophet had frequently received nocturnal revelations commanding him to alter the Pilgrims' strange habits of dress and mode of life. By the time the band reached Ohio, they had shed their skins and donned suits of rags, the more patched and parti-colored the better. "If they wore one whole shoe," Flint noted, "the other one, -- like the pretended pilgrims of old time, -- was clouted and patched." With patch sewed on patch and dirt piled upon dirt, the "state of their assembly," one Lebanonite wrote, "was filthy to the last degree and more disgusting than the solitary abode of the uncultivated savage." 35 Once again the Pilgrims came into contact with the monastic followers of Mother Ann Lee. Two Shaker missionaries from Union Village community near Lebanon had been sent to visit Bullard's followers at Xenia in hopes of changing their allegiance. Responding to the Shakers' invitation, the squalid __________ 31 Daily Advertiser, October 13, 1817; Pittsburgh Gazette, November 4, 1817; Hunt to Sweny, August 20, 1874. 32 American Baptist Magazine, I:342-344. Chase's visit was on November 26, 1817. 33 Ibid., 343. 34 The Philanthropist, January 2, 1818; The Farmer, February 7, 21, 28, March 8, 1818; A Ch[urc]h Journal of current Events by Wallace and Sharp, entry for March 4, 1818. 35 Hunt to Sweny, August 20, 1874; Western Star, March 7, 1818; Flint, Recollections, 276, 277; The Farmer, March 9, 1818. A correspondent whose interview with an unidentified Pilgrim appeared in the latter newspaper noted: "The form of their dress indicated... the most sordid pride in appearing before the world most singularly rediculous [sic] by hanging about them rags and patches where they were not necessary." [ 297 ] Mummyjums arrived at the sequestered Shaker village on March 10. More liberal towards the Pilgrims than their New Lebanon brethren, the Union Village Shakers fed and lodged the group in one of their spacious shops, allowed them to cohabit with their wives or spiritual mates as the case may have been, and gave them permission to exhort in the village meeting house. Patiently the Shakers listened to Bullard's austerity program, but when their hosts tried to do a little proselytizing for which they were justly famous, their guests departed in a huff telling the Shakers that their every word "was of the Devil." 36 FRom this point in their travels, disruption plagued the exodus. Desertions became more frequent. At the village of Mason, a few miles southwest of Union Village, a few members succombed to smallpox. As the Pilgrims approached Cincinnati, the alarmed city fathers, armed with the knowledge of their "affliction by smallpox, and of their extreme filthiness," hurriedly dispatched a committee to request the saints to bypass the town at as "great a distance... as convenience would permit." Nevertheless, the Ohio press had excited the curiosity of the Cincinnatians. On the Sabbath, April 12, thousands of citizens jammed all roads leading to the "seat of filth" and risked health and happiness for a peep at the sooty saints. This spectacle led one of the local wits to caption an account of the Mummyjums with a quotation from Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, "My Oberon! What visions have I seen! Me thought I was enamored of an ass!" 37 In the "Queen City" the Prophet successfully negotiated the sale of their wagons and teams and purchased a flatboat for the water-passage down the Ohio. The Pilgrim's destination was still unknown, even to the Prophet, but it was becoming increasingly clear the Land of Canaan was to be found in trans-Mississippi America. 38 A few weeks later the Mummyjums tied up at the old Spanish garrison town of New Madrid, Missouri, a small depopulated village of some twenty log houses and shops that was devastated during the great earthquake of 1811. In his book, Recollections, Timothy Flint graphically recounted the landing as the Pilgrims waded ashore in Indian file: So formidable a band of ragged Pilgrims marching in perfect order, chanting with a peculiar twang the short phrase, "Praise God! Praise God!" had in it something imposing to a people, like those of the West, strongly governed by feelings and impressions. Sensible people assured me that the coming of a band of these Pilgrims into theor houses affacted them with a thrill of alarm which they could hardly express. The untasted food before them lost its savour, while they heard these strange people call upon them, standing themselves in the posture of statues, and uttering only the words, "Praise God, repent, fast, pray." Small children, waggish and profane as most of the children are, were seen to shed tears, and to ask their parents, if it would not be fasting enough, to leave off one meal a day. 39 So intense was the Pilgrims' hope of inheriting the promised land of Bullard's millennium, that the rigorous discipline, intense privation, and constant penances could be borne for a time. But some measure of chiliastic fulfillment must follow expectation or else disillusionment and disintegration would rend the movement. Wiser prophets such as Mother Ann Lee and the Mormon seer Joseph Smith understood this well. But so inchoate were Bullard's ideas of the coming kingdom that his perfect society could never materialize. As he prolonged the search for the promised land, famine, sickness, and disillusionment produced desertion and disruption. The charismatic spell Bullard had cast over his followers was breaking.

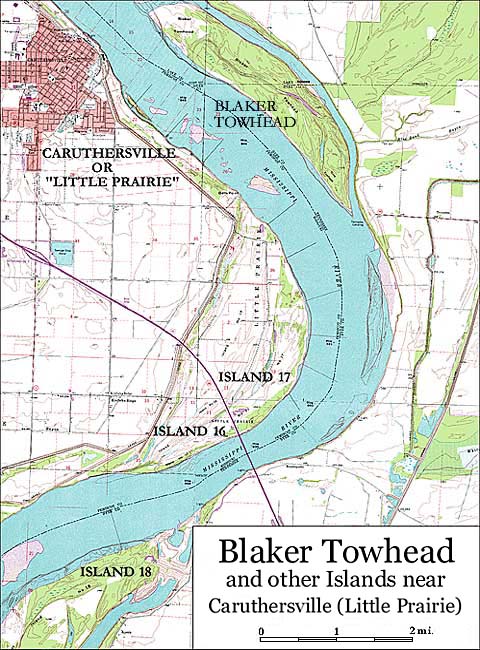

John Hardeman Walker, Esq. (1794-1860) Proprietor of the Pilgrims' Missouri Canaan The Prophet also lacked common sense. __________ 36 Records of the Church at Union Village, Ohio, in Five Books, A-E, Book A, Volume I, entries for February 19, March 10-12, 1818, Shaker Manuscripts, Western Reserve Historical Society. 37 A Ch[urc]h Journal of current Events by Wallace and Sharp, entry for April 6, 1818; Hunt to Sweny, August 20, 1874; Fanny Ball to the Brethren and Sisters at New Lebanon, April 30, 1820; Western Spy (Cincinnati), April 15, 18, 1818. 38 Fanny Ball to the Brethren and Sisters at New Lebanon, April 30, 1820. 39 Flint, Recollections, 277-278. [ 298 ] Any western yeoman would have told him to ascend to the high and healthy regions of Cape Girardeau, Missouri, where his band could acclimate themselves before descending in the summer to the sickly country, but Bullard found "such calculations of worldly wisdom... foreign to their objects." Then too, "suffering was a part of their plan." So the descent continued. 40 Thirty-one miles below New Madrid, the tattered band landed at Pilgrim Island, which derived its name from their coming. Here in a "wilderness inhabited by nothing but wild beasts or savages," the dreaded maladies of the westward movement, wood fever and the ague struck with a fury. Emaciated by hunger and feverish from filth and the climate, many of them left their bones here. In a macabre revelation Bullard was commanded to leave the dead unburied on the beach; a year later Flint observed their bones bleaching on the island. With worsening conditions, the Prophet's autocratic rule became intolerable, and during the summer of 1818 some of his most valued members deserted, including the Ball brothers and several members of their families. 41 While on the island Bullard also had trouble with the Gentiles. After receiving word that starvation was imposed on the children as a discipline, the irate sheriff of New Madrid County arrived with a piroque of provisions, but to feed the "greedy innocents" he had to keep the leaders off with his sword. On another occasion a boat crew taking the saints at their word of having no regard for the things of this world robbed them of their money, while still another account reported that a barge crew from Nashville fell in with the Mummyjums and, detesting the autocratic conduct of the Prophet and his seconds, gave them all "a sound drubbing with a pliant cotton wood switch." 42 Faced with increasing desertions, the Prophet was under extreme pressure to find the Promised Land. Evacuating camp. he landed his band on the west bank of the Mississippi opposite Pilgrim Island at the nearly deserted settlement of Little Prairie. Here the Lord purportedly commanded Bullard to build his church, but the solitary resident and owner of the "Promised Land" interdicted the Almighty's plans. At last the Pilgrims were convinced that the Prophet's powers had failed him. With each saint taking his turn for three successive days and nights they sent up continuously the vociferous cry of "Oh My God, why hast thou forsaken me." 43 The voyage ended one mile below the mouth of the Arkansas River, where their flatboat struck a sand bar. The surviving band of fifteen Pilgrims waded ashore on the west bank. Whether the Lord had spoken or the saints were too exhausted to go on, the search for the promised land had apparently ended. The Land of Canaan was a most forbidding place -- "fit only for the abode of alligators" -- situated on a narrow ridge of land in back of which was a dismal swamp. Unable to get either "corn, pumpkins or milk" the saints abandoned their camp, and moved inland some sixty miles to Port Arkansas, the seat of government for the newly created Arkansas Territory. Here Flint found them in the fall of 1819. The once mighty host had been reduced to six persons -- the Prophet, his wife, another woman, and two children. All were unwell, the Prophet so ill that Flint had to glean what information he could from his wife. 44 The frontier post, moreover, must have smaked too much of a Philistine civilization, for they soon returned to their original station overlooking the Mississippi. Here the renowned naturalist and scientific investigator, Thomas Nuttall, then concluding his Arkansas travels, noted their presence in January, 1820, and learned that an unmitigated disaster had fallen upon the Prophet -- a few days earlier he had been seized by a boat's crew and "forcibly shaved, washed, and dressed." 45 Bullard's experiment had disintegrated in exodus. It was estimated that nearly a half of the Pilgrims perished during the migration. The Shakers' benevolence had not been in vain, for ten saints, including several members of the Ball families, had earlier made their way back to the Union Village community, where they found religious fulfillment and material plentitude/ Even so, remnant remained faithful to the end, lingering out their lives in famine and wretchedness. 46 The last recorded contact with the Pilgrims was in 1824. On a trip to New Orleans, Colonel John Hunt of Warren County, Ohio, stopped to see the last remnants of the sect. He found two young, intelligent, and interesting women (presumably one was the Prophet's wife) dressed in rags and sitting in a hut made of cane reed, bark, and boards. The visitor offered to pay their passage to Cincinnati if they desired to return to their native New England, but the women were steadfast in their faith in the Prophet's revelations. Having at long last found the Promised Land, they told Hunt "nothing on earth would induce them to leave it." 47 The Pilgrims were a minor religious aberation. Nevertheless this curious and unknown search for the perfect society helps to explain the prevalence and source of religious ultraism in their period. Further, it helps explain why many distraught revivalists, in their search for a life free from sin and their belief in the nearness of the millennium, fell prey to any prophet who might promise messianic fulfillment. It also documents de Tocqueville's observation that "religious insanity is very common in the United States." 48 __________ 40 Ibid., 279 41 Wayne Sentinel, May 26, 1826; Fanny Ball to the Brethren and Sisters at New Lebanon, April 30, 1820; Flint, Recollections, 278; Thompson, History of Vermont, II:204. 42 Flint, Recollections, 279; Wayne Sentinel, April 26, 1826. 43 Fanny Ball to the Brethren and Sisters at New Lebanon, April 30, 1820; Wayne Sentinel, April 26, 1826. This latter account claims that at Little Prairie one of the band absconded with all the Pilgrims' cash. 44 Ibid.; Hunt to Sweny, August 20, 1874; Flint, Recollections, 275. 45 Thomas Nuttall, Journal of Travels into the Arkansas Territory During the year 1819, edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites (Cleveland, 1905), 294-295. 46 Flint, Recollections, 279-280; Fanny Ball to the Brethren and Sisters at New Lebanon, April 30, 1820; Records Kept by the Order of the Church, New Lebanon, New York, 52. The fate of the Prophet is unknown. Later accounts, such as those in the Western Balance, Thompson's History of Vermont, and John Hunt, all claim Bullard sied at New Madrid, but both Flint and the Ball letter disprove their statements. 47 Hunt to Sweny, August 20, 1874. The following year, 1825, Hunt again stopped at the mouth of the Arkansas and White rivers and asked about the fate of the two women. He was told that one had died and the other had left for New Oreleans in an attempt to return to New England. 48 Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 342. |

|

Transcriber's Comments

|

|

"Modern Pilgrims Research Resources

Vol. ? Arkansas Post, A. T., early 1820s? No. ? These Pilgrims never worked, bathed, washed their clothes, or cut or combed their hair. Their food, when they could get it, was corn meal mush and milk, which they sucked up from troughs through perforated stalks of cane. Their prophet, who is now dead, had night visions which directed their course of march. When entering a town, the Pilgrims walked in Indian file, chanting “Praise God! Praise God!” in a kind of tune. Passing through Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, the Pilgrims at length found their way down the Mississippi to the mouth of the Arkansas. Most of them have died of fever and starvation; one was found dead in the road which leads to this place. It is contrary to their doctrine to bury their dead; so their bones lie bleaching in many locations from here to Canada. According to reports, there now exists of this fanatic band only one man, three women and two children. The man was recently seized by a boat’s crew and forcibly shaved, washed and dressed. Note: The above text may be only a modern "recreation" of an old news article -- or it may be based upon an actual report from an early 1820s issue of the Arkansas Gazette. The account of Isaac Bullard's being washed and shaved by a passing riverboat's crew, was published in the 1905 Thomas Nuttall book, Journal of Travels into the Arkansas Territory During the year 1819. Vol. 106. Zanesville, Ohio, Sunday, July 6, 1969 No. 145. Conducted Meeting in Front of Courthouse Bearded Prophet Visited Zanesville in 1817 A Prophet with long beard and flowing robe pounded his shepherd's staff on the ground with every step as he walked down Zanesville's Main street in 1817. Like all his followers in wagons and on foot he wore a bearskin girdle as the symbol of his sect. The members of this fanatical band cited scripture to prove that they would never die, and they claimed divine authority to practice free love. Turning south on Fifth street from Main, the followers of this self-styled "second Moses" and "high priest" pitched their tents at the southwest corner of Locust alley and Fifth street. The Zanesville Federal Savings & Loan Building is located there today. AFTER PITCHING camp they held a meeting in front of the old Courthouse. The men spoke in "unknown tongues" and the women worshipped by lying face downward on the ground and threshing their arms. These religious fanatics called themselves Vermont Pilgrims. Their leaders heard the voice of God in lower Canada in the summer of 1817. There they administered "by command of the Lord" a decoction of poisonous bark to an infant. The child died and they were placed on trial for murder. They quickly departed from Canada. Coming south to Woodstock, Vermont, they held meetings and added several proselytes to their number. All new members "assumed the girdle of bearskin" while the Prophet mumbled in a "foreign tongue." FROM VERMONT the Pilgrims traveled south through New Jersey, [West] Virginia and Eastern Ohio to Zanesville. Under the direction of "the spirit of God" they were headed for the town of Pike on Derby Creek. But they remained in Zanesville about two weeks in November, 1817. That was long enough for them to make a strong impression on the community and to leave a fantastic page of local folklore. Boys and men gathered around the south Fifth street camp. They were fascinated with the power of the Prophet named Ballard [sic - Bullard?] over his converts. ONE ACCOUNT said of the Prophet, "He rejects surnames, and abolished marriage, and always has his followers cohabit promiscuously. The men eat their food in an erect posture, and the women, when they pray, prostrate themselves on the ground with their faces downwards." Zanesville boys listened to the "hof Latin" of these fanatics and watched their queer actions. Then they taunted them by singing this doggerel: "Hark, hark, the dogs do bark, ADULTS WERE SHOCKED by the teachings of the Pilgrims. When the band of 30 or 40 fanatics arrived here, the Zanesville "Express" said: "Their object, they say, is the good of mankind. Their Prophet announces that he has the power of casting out devils and that he intends shortly to commence business." The editor concluded that if the Prophet possessed the power he claimed, "he would have found sufficient employment at home." If Zanesville boys were amused and their parents shocked by the Pilgrims, we can be sure that the clergy were horrified. It must have been a minister who wrote the following letter to the Zanesville "Express" on Nov. 20, 1817, and signed it "A Reader." "On their first arriving in town, a meeting was notified at the Courthouse, in this place, where an exhortation was given by one of their party, Mr. Holmes, the only man of any considerable talents among them, who has been a Methodist preacher about 12 years in Vermont. THE PILGRIMS made one convert in Zanesville. He "took the bearskin girdle" as a passport to the promised land. His two brothers-in-law followed the band and persuaded their realtive to return. E. H. Church wrote an account of the Vermont Pilgrims for the [Zanesville] Courier in 1880. Capt. John Dulty, then living in Zanesville, told Church that, as he was crossing the mountains in 1818, he overtook a woman carrying a bundle. Dulty thought he had seen her in Zanesville with the Pilgrims. She admitted that she had been a follower of the Prophet. Ballard's band followed him until they were warned away from the Darby Plains in Ohio. When the Prophet suddenly changed the location of the Promised Land to the Arkansas canebrakes, some of his followers decided they did not want to go there after all. The former Pilgrim told Dulty that she was going back home to Vermont. The inhabitants of the little town of Zanesville in 1817 did not witness the raising of the dead but they did see a preview of the unkempt hippie appearance and an attempt to destroy all civil establishments, that have [re]appeared in 1969.

Warren County Local History:

(Bowie, MD: Heritage Press, 1979) p. 100 A radical sect of religious extremists, organized about 1817, passed through Warren County, their projectory extending from the Eastern States to the vicinity of Arkansas. Their leader and Prophet, Isaac Buller [sic], was a native of the New England States. Mr. Buller had a spine injury, which was caused from the effects of a fall, which in turn caused partial paralysis. He was confined to bed for many months because of the painful effect. His devout neighbors had repeatedly met in his room and had prayer concerning his recovery. During one of these episodes, he immediately stated his pain was gone and he was restored to complete health. With absolute pain-free insistence, he was now able to walk with two canes. An announcement was made that the Lord had healed him, and made him His Prophet. Many of the prayerful had believed this act was the intercession of Providence. The new Prophet, now pain-free, told his flock that through the intervention of the Lord, he would lead them to the Promised Land. This new religion was embraced not only by the common folk, but also by the wealthy, and people of high social standing. The Prophet positioned his cane in an upright position and let it fall. This was a sign of the path the new sect would take. The cane always fell in a southwest direction. Loading of wagons, teams, a minimal supply of clothes, beds, food and cooking contrivance was for their journey. First, they made their way from New England to New York, and, a year later, they reached Lebanon, Ohio. Their journey was full of revelations by the Prophet, presumably from the Lord, directing the followers to change their way of habit of dress and manner of life. Bathing was outlawed as was washing their clothes. No allowances were made concerning excessive material objects. Their clothing was very minimal, only enough to keep away the cold. The only meat allowed was raw bacon. "Filth, rags and wretchedness" were a need for them to reach the Promised Land. Their arrival in Warren County was a despicable sight. Some of the more intelligent members of the band had quite readily figured Prophet Buller for an impostor. They in turn returned to New England, or picked out spots along their route to make their homes. The remainder, who stayed in Lebanon, held public gatherings for worship. At these meetings, the Prophet and other speakers warned the people to avoid all pride and everything worldly in dress and food. The speakers at the meetings would utter these words: "Oh-a, Ho-a, Oh-a, Ho-a - My God, My God, My God!" The congregation would in turn repeat the words. The Prophet and his people traveled from Lebanon to Union Village and remained several days. The Shakers remarked in their notes that the first time they heard of the clan was at Xenia. Two of the Shakers ventured to see them on the 19th of February 1818. The Pilgrims, on the tenth of March, being only fifty-five in number, reached Union Village. The brethren kindly received them and fed them and their horses. A meeting was called at the church; it was held by five of the Pilgrims of which three men and two women preached. After the preaching the strange clan quickly withdrew. They had been assigned a single room by the Shakers, in which to lodge, and sent some of their preachers to speak to them, but to no avail, the leaders of the Pilgrims shunned them. The next day, their gratitude was expressed and they set out again for the Promised Land. Mason was next in line for the visitation of the sect. While in this neighborhood, the smallpox broke out and caused many deaths among them. Still following the direction of the falling cane, they arrived in New Madrid, Mo., where the Prophet became ill and died. Before his death, he promised to return to them in two years, and for them to continue their journey. The frail band at last found the Promised Land, which was located on the west bank of the Mississippi, not far from the mouth of the Arkansas River. In 1824, Hon. John Hunt traveled to New Orleans in a flatboat, accompanied by two other flatboats along with their crews. They stopped at the mouth of the Arkansas to inquire about the fate of the Pilgrims. The Promised Land consisted of a narrow ridge of dry land, almost surrounded by a swamp, a most decrepit place for habitation. The remainder of Buller's clan consisted of two ladies living in a wretched tent, made with forks and poles, reed cane and bark. They were neatly dressed and spoke with a very intelligent keenness; still they claimed the reverence of the Prophet's religion. Mr. Hunt offered a sum of money for their transportation by steamboat to Cincinnati, but they thanked him and refused his service. Mr. Hunt, during a later trip down the Mississippi, learned that one of the ladies had died and the destiny of the other was unknown. (under construction) |

|

Bibliography of Published Sources 1817 (Sept.-Oct.)Sept. 15 Newton, NJ Sussex Register (text from reprint) Sept. 22 Bridgeton, NJ Washington Whig Sept. 23 Troy, NY The Budget (no text for link) Oct. ? Rutland, VT Rutland Herald (no text for link) Oct. Philadelphia New Jerusalem Repository Oct. 13 New York Albany Daily Advertiser (text from reprint) Oct. 14 Brattleboro, VT American Yeoman (no text for link) Oct. ? Richmond Virginia Patriot (no text for link) Oct. 28 Elizabeth-Town, NJ New-Jersey Journal Oct. 28 Pittsburgh Gazette 1817 (Nov.-Dec.) Nov. 3 Bridgeton, NJ Washington Whig Nov. 4 Pittsburgh Gazette Nov. 24? Zanesville Express (text from reprint) Nov. 5 Chillicothe Weekly Recorder Nov. 12 Chillicothe Weekly Recorder Nov. 26 Chillicothe Weekly Recorder Dec. 8 Carlisle, Pa. Spirit of the Times & Carlisle Gazette 1818 (Jan.-Feb.) Jan. 2 Mount Pleasant, Ohio The Philanthropist (no text for link) Jan. 28 Urbana, Ohio Urbana Gazette (text from reprint) Feb. 7 Lebanon, Ohio The Farmer (no text for link) Feb. 21 Lebanon, Ohio The Farmer (no text for link) Feb. 28 Lebanon, Ohio The Farmer (no text for link) 1818 (Mar.-Apr.) Mar. 7 Lebanon, Ohio Western Star (no text for link) Mar. 8? Lebanon, Ohio The Farmer (no text for link) Mar. 9? Lebanon, Ohio The Farmer (no text for link) Mar. 19 Carlisle, Pa. Spirit of the Times & Carlisle Gazette Apr. 15 Cincinnati Western Spy (text from reprint) Apr. 18 Cincinnati Western Spy (no text for link) 1818 (May-Dec.) May ? Cincinnati Bee (no text for link) May American Baptist Magazine May 12 Newark, NJ Sentinel of Freedom May 22 Danville, VT North Star (no text for link) 1819 (Jan-Dec.) (no articles yet located) 1820 (Jan-Dec.) Jan. ? Boston Christian Watchman (text from reprint) Jan. 11 Carlisle, Pa. Carlisle Republican Jan. 26 Philadelphia Union (text from reprint) Feb. 9 Massachusetts Pittsfield Sun Feb. 15 Vermont Woodstock Observer 1821-1829 1822 Oct. 5 Philadelphia Saturday Evening Post 1826 late April Franklin, Tennessee Western Balance (no text for link) 1826 May 6 NYC The Telescope 1826 May 26 Palmyra Wayne Sentinel 1826 no date Timothy Flint's Recollections of the Last Ten Years... in the Valley of the Mississippi (no text for link) 1828 May 22 Warren, Ohio Western Reserve Chronicle 1830-1869 1831 June 24 Woodstock Vermont Chronicle 1842 no date Zadock Thompson's History of Vermont 1880-1899 1880 no date E. H. Church account in Zanesville Courier (no text for link) Note: This episode was reprinted in Elijah Hart Church's Early History of Zanesville... Stories from the Zanesville Courier 1874-1880, edited by Jeff Carskadden, (Salt Lake City Family History Library: 977.191/Z1 H2c, 1986) 1882 no date Josiah Morrow The History of Warren County, Ohio 1897 no date John R. Musick's Stories of Missouri (no text for link) 1898 no date George B. Goodrich's Centennial History of the Town of Dryden, 1797-1897 1900-1999 1921 no date W. B. Stephens' Centennial History of Missouri (no text for link) 1939 no date David M. Ludlum's Social Ferment in Vermont 1791-1850 1957 no date J. S. Garrett's "Caruthersville Centennial Pagent" (no text for link) 1959 no date Savoie Lottinville's A Journal of Travels into the Arkansas Territory during the Year 1819 (no text for link) 1961 no date J. S. Garrett's Bountiful Bootheel Borning (no text for link) 1962 no date F. Gerald Ham's "Shakerism in the Old West" (chp. 7 "Socialists, Saints and Seers") (no text for link) 1969 July 6 Norris F. Schneider's "Bearded Prophet Visited Zanesville" 1973 summer F. Gerald Ham's "The Prophet and the Mummyjums" 1979 no date Dallas Bogan's "Passing of the Pilgrims" 2000-2006 2003 no date Stephen J. Stein's Communities of Dissent: A History of Alternative Religions (no text for link) |

return to top of page

OPENING NEW HORIZONS IN MORMON HISTORY

last updated: Apr. 9, 2006